In February, the city of Toronto announced plans for a new development along its waterfront. They read like a wish list for any passionate urbanist: 800 affordable apartments, a two-acre forest, a rooftop farm, a new arts venue focused on indigenous culture, and a pledge to be zero-carbon.

The idea of an affordable, off-the-grid Eden in the heart of the city sounds great. But there was an entirely different urban utopia planned for this same 12-acre plot, known as Quayside, just a few years ago. It was going to be the place where Sidewalk Labs, the urban innovation arm of Alphabet, was going to prove out its vision for the smart city.

Sandwiched between the elevated Gardiner Expressway and Lake Ontario, and occupied by a few one-story commercial buildings and a mothballed grain silo, Quayside shouldn’t have been that hard to develop. But controversy ensued almost from the moment in October 2017 that Waterfront Toronto, a governmental agency overseeing the redevelopment of 2,000 acres along the lake shore, announced that Sidewalk had submitted the winning proposal.

Sidewalk’s big idea was flashy new tech. This unassuming section of Toronto was going to become a hub for an optimized urban experience featuring robo-taxis, heated sidewalks, autonomous garbage collection, and an extensive digital layer to monitor everything from street crossings to park bench usage.

Had it succeeded, Quayside could have been a proof of concept, establishing a new development model for cities everywhere. It could have demonstrated that the sensor-laden smart city model embraced in China and the Persian Gulf has a place in more democratic societies. Instead, Sidewalk Labs’ two-and-a-half-year struggle to build a neighborhood “from the internet up” failed to make the case for why anyone might want to live in it.

By May 2020, Sidewalk had pulled the plug, citing “the unprecedented economic uncertainty brought on by the covid-19 pandemic.” But that economic uncertainty came at the tail end of years of public controversy over its $900 million vision for a data-rich city within the city.

It’s hardly unusual for citizens to get up in arms about new development, and utopias fail for all sorts of reasons. But the opposition to Sidewalk’s vision for Toronto wasn’t about things like architectural preservation or the height, density, and style of the proposed buildings—the usual fodder for public outcry. The project’s tech-first approach antagonized many; its seeming lack of seriousness about the privacy concerns of Torontonians was likely the main cause of its demise.

There is far less tolerance in Canada than in the US for private-sector control of public streets and transportation, or for companies’ collecting data on the routine activities of people living their lives.

The shift signaled by the new plan, with its emphasis on wind and rain and birds and bees rather than data, seems like a pragmatic response to the present moment.

“In the US it’s life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness,” says Alex Ryan, a senior vice president of partnership solutions for the MaRS Discovery District, a Toronto nonprofit founded by a consortium of public and private funders and billed as North America’s largest urban innovation hub. “In Canada it’s peace, order, and good government. Canadians don’t expect the private sector to come in and save us from government, because we have high trust in government.”

With its very top-down approach, Sidewalk failed to comprehend Toronto’s civic culture. Almost every person I spoke with about the project used the word “hubris” or “arrogance” to describe the company’s attitude. Some people used both.

The end of the smart city?

Time and time again, we convince ourselves that the big idea of the moment will not only improve our daily lives but cure society’s ills. In England, the “garden city” movement introduced by the urban planner Ebenezer Howard in 1898 aimed to merge the countryside and the city while avoiding the disadvantages presented by both. The American version, the City Beautiful, sought to return beauty and grandeur to cities as a path to a more harmonious social order. Le Corbusier’s rigid, high-density plan for the never-built Ville Radieuse (Radiant City) in Paris pursued urban utopia through architectural discipline. More recently, the “15-minute city” is a global movement in favor of planning cities so that everyone has access to work, school, retail, and recreation within a 15-minute walk or bike ride.

The smart city has been perhaps the dominant paradigm in urban planning over the past two decades. The term was originally coined by IBM in hopes that technology could improve the way cities functioned, but as a strategy for city-building, it’s been most successfully deployed under authoritarian regimes (Putin is a fan). Critics say it tends to overlook the importance of human beings in the quest for technological solutions. Even when the architectural renderings were fabulous, the idea of the smart city has always had problems. The phrase itself suggests that existing cities are lacking in brain power, even though they have—throughout human history—been incubators for culture, ideas, and intellect.

The real problem is that with their emphasis on the optimization of everything, smart cities seem designed to eradicate the very thing that makes cities wonderful. New York and Rome and Cairo (and Toronto) are not great cities because they’re efficient: people are attracted to the messiness, to the compelling and serendipitous interactions within a wildly diverse mix of people living in close proximity. But proponents of the smart city embraced instead the idea of the city as something to be quantified and controlled.

Smart city technology should do things like shorten commute times, speed the construction of affordable housing, improve the efficiency of public transit, and reduce carbon emissions by making building technology more efficient and providing less polluting transportation alternatives to the car. But often its proponents focus on what it can do rather than what it should. If Sidewalk’s Quayside failure taught us anything, it’s that these technologies need to respond better to human needs.

The first reactions to the Sidewalk project were, if not rapturous, still quite optimistic. Alex Bozikovic, the architecture critic for Toronto’s Globe and Mail, believed Sidewalk Labs might offer a more exciting approach to development. This very publication included the project as one of its 10 breakthrough technologies in 2018, writing that “Sidewalk Labs could reshape how we live, work, and play in urban neighborhoods.”

But over time, even the people who should have been Quayside’s allies and boosters felt increasingly alienated. “There was a hubris to the way that they thought that they could solve all the problems in house,” says the MaRS Discovery District’s Ryan, whose job is to promote “innovation for the benefit of all.”

By 2020 the project, which had yet to break ground, seemed increasingly untenable. And on May 7, two weeks before the Waterfront Toronto board was scheduled to take a vote on whether to shut it down, Sidewalk walked.

Sidewalk CEO Dan Doctoroff posted a farewell letter on Medium explaining that it had “become too difficult to make the 12-acre project financially viable without sacrificing core parts of the plan we had developed together with Waterfront Toronto to build a truly inclusive, sustainable community.” He added: “And so, after a great deal of deliberation, we concluded that it no longer made sense to proceed with the Quayside project.”

Most Quayside watchers have a hard time believing that covid was the real reason for ending the project. Sidewalk Labs never really painted a compelling picture of the place it hoped to build.

Quayside 2.0

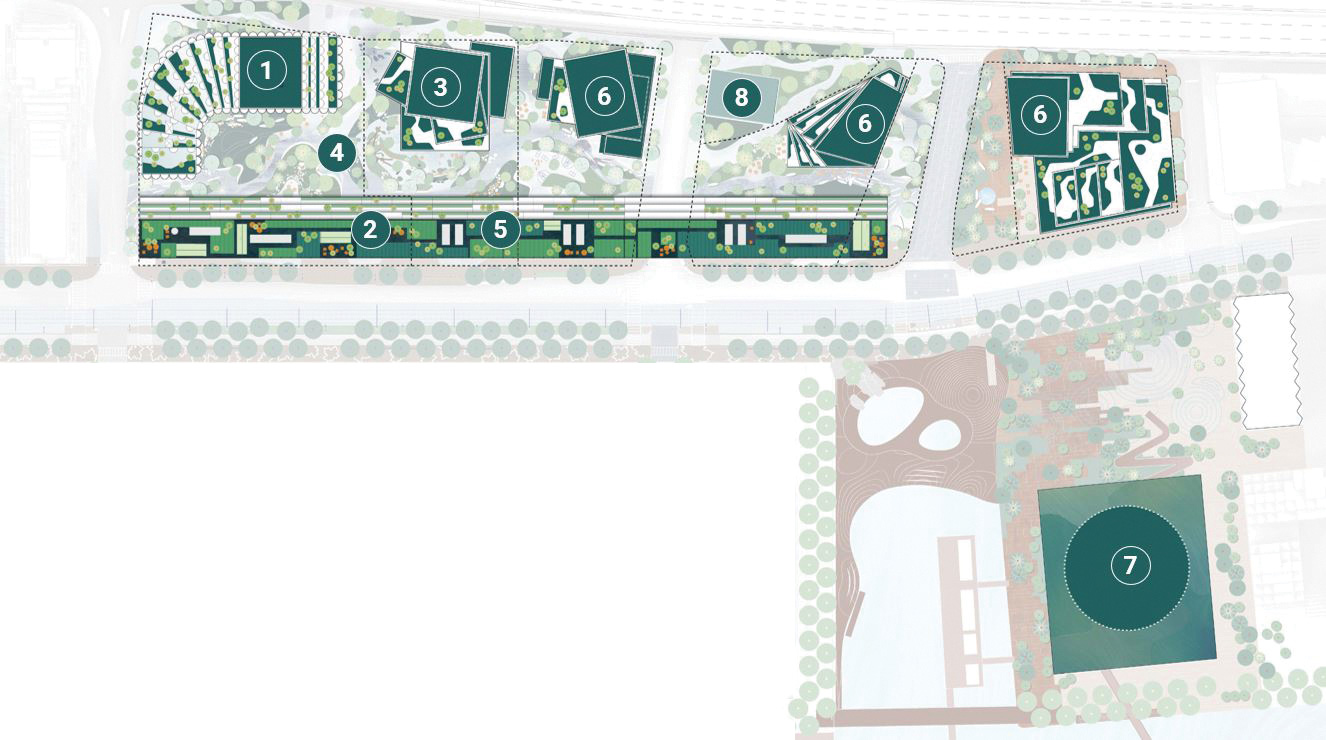

The new Waterfront Toronto project has clearly learned from the past. Renderings of the new plans for Quayside—call it Quayside 2.0—released earlier this year show trees and greenery sprouting from every possible balcony and outcropping, with nary an autonomous vehicle or drone in site. The project’s highly accomplished design team—led by Alison Brooks, a Canadian architect based in London; the renowned Ghanaian-British architect David Adjaye; Matthew Hickey, a Mohawk architect from the Six Nations First Nation; and the Danish firm Henning Larsen—all speak of this new corner of Canada’s largest city not as a techno-utopia but as a bucolic retreat.

In every way, Quayside 2.0 promotes the notion that an urban neighborhood can be a hybrid of the natural and the manmade. The project boldly suggests that we now want our cities to be green, both metaphorically and literally—the renderings are so loaded with trees that they suggest foliage is a new form of architectural ornament. In the promotional video for the project, Adjaye, known for his design of the Smithsonian Museum of African American History, cites the “importance of human life, plant life, and the natural world.” The pendulum has swung back toward Howard’s garden city: Quayside 2022 is a conspicuous disavowal not only of the 2017 proposal but of the smart city concept itself.

To some extent, this retreat to nature reflects the changing times, as society has gone from a place of techno-optimism (think: Steve Jobs introducing the iPhone) to a place of skepticism, scarred by data collection scandals, misinformation, online harassment, and outright techno-fraud. Sure, the tech industry has made life more productive over the past two decades, but has it made it better? Sidewalk never had an answer to this.

“To me it’s a wonderful ending because we didn’t end up with a big mistake,” says Jennifer Keesmaat, former chief planner for Toronto, who advised the Ministry of Infrastructure on how to set this next iteration up for success. She’s enthusiastic about the rethought plan for the area: “If you look at what we’re doing now on that site, it’s classic city building with a 21st-century twist, which means it’s a carbon-neutral community. It’s a totally electrified community. It’s a community that prioritizes affordable housing, because we have an affordable-housing crisis in our city. It’s a community that has a strong emphasis on green space and urban agriculture and urban farming. Are those things that are derived from Sidewalk’s proposal? Not really.”

Jennifer Keesmaat, former chief planner for Toronto (left), and Alex Ryan and Yung Wu of MaRS, North America’s largest innovation hub (all of whom are working on the new waterfront project), believe that less tech reliance and more civic engagement could be the new way forward.

Indeed, the philosophical shift signaled by the new plan, with its emphasis on wind and rain and birds and bees rather than data and more data, seems like a pragmatic response to the demands of the present moment and the near future. The question is whether this new urban Eden truly offers a scenario that will rein in global warming or whether it’s “green” the way a smart city is “smart.” How many pocket forests and neighborhood farms will it take to cool the planet?

Whatever its practical impact, renderings of the new version of Quayside suggest a more livable place. The development promises something incredibly obvious that the purveyors of the smart city missed: a potential for daily life to be pleasurable. As MaRS Discovery District CEO and tech entrepreneur Yung Wu puts it: “What is the vision that inspires people to want to live here, to work here, to raise their families and children and grandchildren here? What is it that inspires that?”

“It’s not a smart city,” he concludes. “It’s a city that’s smart.”

Karrie Jacobs writes about design, architecture, and cities for Curbed, Architect, and the New York Times.

from MIT Technology Review https://ift.tt/bHY0Qk4

via gqrds

Comments

Post a Comment