When the designer and typographer Marcin Wichary stumbled upon a tiny museum just outside Barcelona five years ago, the experience tipped his interest in the history of technology into an obsession with a very particular part of it: the keyboard.

“I have never seen so many typewriters under one roof. Not even close,” he shared on Twitter at the time. “At this point, I literally have tears in my eyes. I’m not kidding. This feels like a miracle.”

He’d had a revelation while wandering through the exhibit: Each key on a keyboard has its own stories. And these stories are not just about computing technology, but also about the people who designed, used, or otherwise interacted with the keyboards.

Take the backspace key, he explains: “I like that [the concept of] backspace was originally just that—a space going backward. We are used to it erasing now, but for a hundred years, erasing was its own incredibly complex endeavor. You needed to master a Comet eraser, or Wite-Out, or strange correction tapes, and possibly all of the above … or give up and start from scratch whenever you made a typo.”

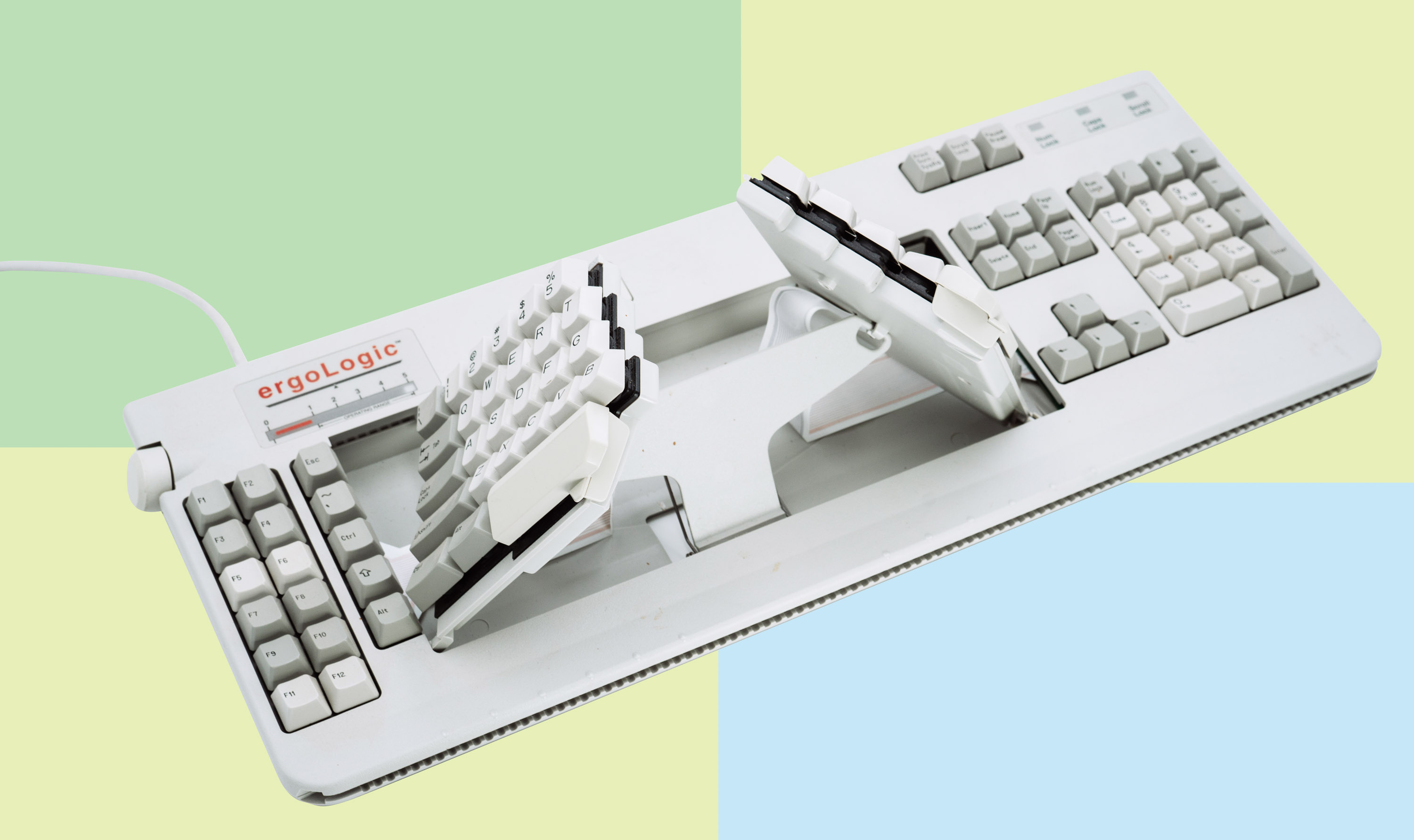

These days, even the cheapest desk keyboard is in some way “ergonomic,” allowing for reduced effort and improved response compared with even the best of the mechanical and electric typewriters that preceded them. But some keyboards go further than most, rotating or tenting their respective halves to allow a less stressful hand and arm position.

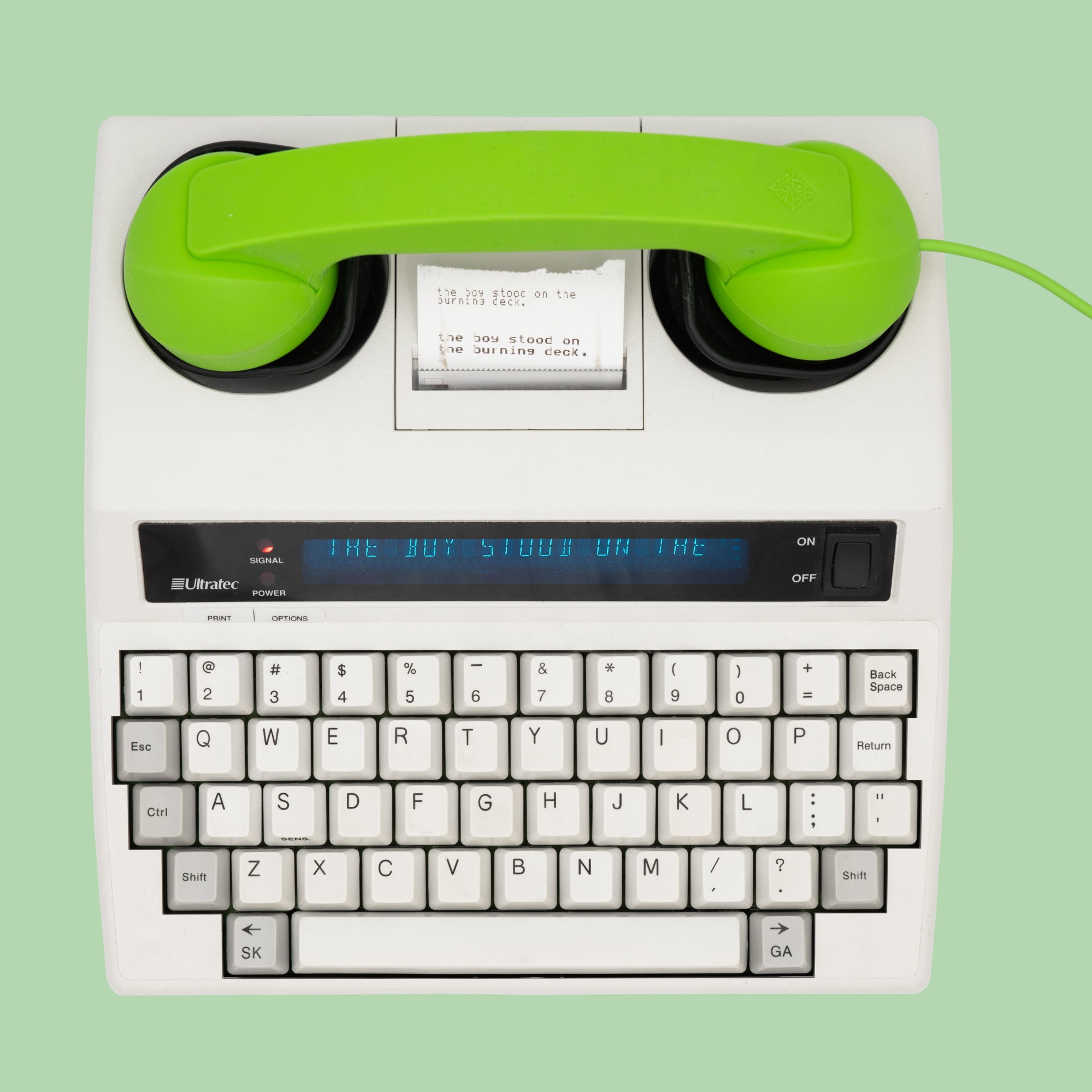

Some keyboards enable communication between people who might find that difficult. Shown here are a simple keyboard connected to a singular Braille cell; a typewriter making it possible to print in Braille; and a machine that allowed people who are hard of hearing to type over telephone wires.

The deeper he researched, the more fixated he became. Amazed that no comprehensive book existed on the history of keyboards, he decided to create his own. When not working at his day job as design lead for the design software company Figma, he began producing Shift Happens, a two-volume, 1,216-page hardcover book—and raised over $750,000 for the project on Kickstarter in March of 2023. Wichary was only a bit surprised by the support and the keyboard’s wide appeal. As he points out, “It’s such a crucial device that occupies a lot of our waking life.”

from MIT Technology Review https://ift.tt/Em5DqF2

via gqrds

Comments

Post a Comment